President Bola Tinubu granted a presidential pardon to Maryam Sanda on October 11, 2025, freeing the 37-year-old woman who spent six years and eight months on death row for killing her husband.

The controversial decision sparked renewed debate about justice, domestic violence, and presidential mercy in Nigeria, as Sanda walked free from Suleja Medium Security Custodial Centre based on good conduct, remorse, and family pleas citing her two young children.

Her case, from the brutal stabbing death of Bilyaminu Bello in 2017 to her release eight years later, is one of Nigeria’s most high-profile domestic violence cases, exposing the deadly intersection of jealousy, privilege, and violence within elite society.

The pardon came after the Presidential Advisory Committee on Prerogative of Mercy recommended clemency, and the Council of State approved it on October 10, 2025. Sanda was among 175 convicts and former convicts granted mercy in what officials described as one of the most expansive uses of presidential clemency in recent Nigerian history, including posthumous pardons for Ken Saro-Wiwa and Major General Mamman Vatsa.

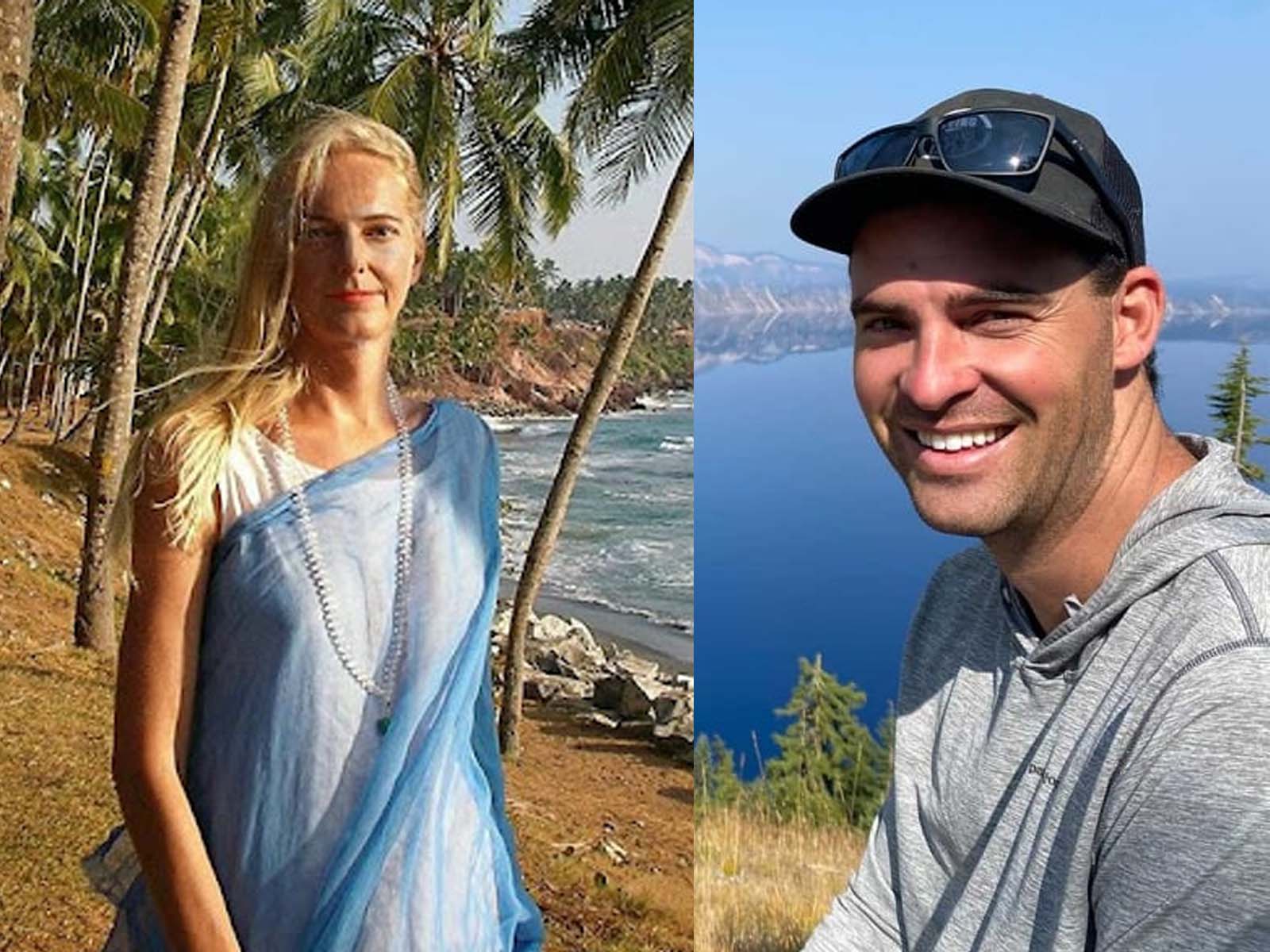

Maryam Sanda Biography

Maryam Sanda (born 1988, 37) grew up in the rarefied air of Northern Nigeria’s political and business elite.

Her mother, Maimuna Aliyu, served as Executive Director of Aso Savings and Loans Plc and moved in influential financial circles. In 2017, Aliyu was nominated to the board of the Independent Corrupt Practices Commission, though the nomination was withdrawn after corruption allegations emerged.

The Independent Corrupt Practices and Other Related Offences Commission later charged her with defrauding Aso Savings and Loans of N57 million (approximately $360,000), though she was eventually acquitted.

Maryam’s marriage to Bilyaminu Bello connected two prominent Northern Nigerian families. Her husband’s father, Dr Haliru Mohammed Bello, served as Acting National Chairman of the People’s Democratic Party and held cabinet positions, including Minister of Communications and Minister of Defence. A veterinary surgeon by training, the elder Bello also served as Comptroller General of the Nigerian Customs Service from 1988 to 1994.

The couple lived in Maitama/Wuse 2, among Abuja’s most affluent neighbourhoods, and employed household staff, including a housemaid and laundryman. They had their first child, a daughter, around May 2017, just six months before the fatal incident that would destroy their family. Despite her privileged background, specific details about Maryam’s education and professional career before marriage remain undocumented in public sources.

Maryam Sanda Crime

The fatal confrontation occurred in the early morning hours of November 19, 2017, at the couple’s home on 4 Pakali Close in Wuse 2, Abuja. According to court testimony, Maryam discovered nude photographs of another woman on her husband’s phone, triggering a violent rage that would end in death.

Ibrahim Mohammed, a close friend of Bilyaminu who was present at the home earlier that evening, provided chilling testimony about the escalating violence. He told the court he had to retrieve a knife from Maryam three or four times during the evening as she repeatedly threatened to cut off her husband’s private parts. Mohammed left after the couple appeared to calm down, but the fatal attack occurred shortly after his departure, around 3:50 AM.

Neighbours heard Bilyaminu crying for help and saw him crawling from a room, bleeding from multiple stab wounds to his chest and neck. The laundryman, Hamza Abdullahi, helped transport the dying man to Maitama General Hospital, where he was pronounced dead. When they returned to the scene, the bloodstains had been mysteriously cleaned, evidence that would later become central to the prosecution’s case.

Maryam claimed the death was accidental, asserting that during their argument, Bilyaminu pushed her, causing her to fall and break a shisha pot. She said water spilt on the floor, her husband slipped, and fell onto the broken shards, which pierced his chest. The court would ultimately reject this explanation as a fabrication.

Delayed Justice

Maryam Sanda was arrested and arraigned on November 24, 2017, just five days after her husband’s death.

The court initially denied bail repeatedly, remanding her to Suleja Prison in Niger State. But in February 2018, she revealed she was three months pregnant, expecting her second child, while facing murder charges.

In March 2018, Justice Yusuf Halilu finally granted bail on health grounds, noting that Maryam was a nursing mother with asthma and that prison facilities were inadequate for her pregnancy and delivery needs. She gave birth to a son on August 7, 2018, naming him Bilyaminu after his deceased father, according to Islamic tradition.

The trial stretched over two years, marked by disappearing witnesses, attorney withdrawals, and repeated delays.

Joseph Bodunde Daudu, a Senior Advocate of Nigeria and former President of the Nigerian Bar Association, initially represented Maryam but withdrew from the case in October 2018. Joe Gadzama, another Senior Advocate, took over the defense.

The prosecution called six witnesses but presented no murder weapon, no autopsy report, and no eyewitness to the actual killing.

Instead, they relied on circumstantial evidence and the legal “Doctrine of Last Seen”, since Maryam was the last person with her husband and failed to explain his death adequately. Three co-defendants initially charged with tampering with evidence, including Maryam’s mother and brother, were discharged and acquitted in April 2019.

Maryam Sanda Death Sentence

On January 27, 2020, after a judgment lasting nearly three hours, Justice Yusuf Halilu delivered his verdict: guilty of culpable homicide punishable by death. The judge rejected Maryam’s shisha pot story as a “smokescreen hatched to mislead the court and cover the truth,” finding that she had stabbed her husband with a kitchen knife “in cold blood.”

“I have come to the irresistible conclusion that you Maryam Sanda is guilty of the murder of Bilyaminu your husband whom you have indeed killed in cold blood,” Justice Halilu declared. He continued with stark biblical language: “It has been said that thou shall not kill. Whoever kills in cold blood shall die in cold blood. It is blood for blood.”

The courtroom erupted in chaos. Maryam fled the dock screaming, “Who will take care of my daughter?” and attempted to reach the balcony before security restrained her. She covered her face with a black veil as she was dragged from the courtroom, her body shaking violently. Family members burst into tears and wail. The judge called a short recess to restore order before pronouncing the death sentence: hanging until she dies.

Justice Halilu offered no mercy despite her two young children, stating that “the rising crime of mindless and senseless killings of men and women in our society leaves much to be desired” and that sentiment could not override the law. Under Section 221 of the Penal Code, the death penalty for culpable homicide is mandatory.

Appeals

Maryam’s legal team filed 20 grounds of appeal, arguing the trial judge was biased, the conviction relied solely on circumstantial evidence without physical proof, and that Justice Halilu had overstepped his judicial role by “usurping the role of police” in investigating the case. They pointed to the absence of a confessional statement, murder weapon, and autopsy report determining the true cause of death.

On December 4, 2020, a three-member panel of the Court of Appeal led by Justice Stephen Adah dismissed all 20 grounds as lacking merit. In a two-hour judgment, the appellate court upheld both the conviction and death sentence. “The circumstances surrounding the death can be the best proof of what is being alleged,” Justice Adah stated, affirming that the trial court was correct and the crime was punishable by death.

Defense counsel announced plans to appeal to the Supreme Court, and the case was eventually scheduled for hearing before a five-member Supreme Court panel in December 2022. However, no definitive Supreme Court judgment was reported before the presidential pardon intervened, effectively ending the legal proceedings.

Presidential pardon

The turning point came during a Council of State meeting on October 10, 2025, when President Bola Tinubu presented recommendations from the Presidential Advisory Committee on the Prerogative of Mercy, chaired by Attorney-General Lateef Fagbemi. The Council, comprising the President, Vice President, all former Presidents and Heads of State, former Chief Justices, the Senate President, House Speaker, all state Governors, and the Attorney-General, unanimously approved clemency for 175 individuals.

Presidential spokesman Bayo Onanuga announced the pardons on October 11, 2025, explaining that Maryam’s family had “pleaded for her release, arguing that it was in the best interest of her two children.” The plea was anchored on her good conduct in jail, demonstrated remorse, and “embracement of a new lifestyle, demonstrating her commitment to being a model prisoner.”

The clemency exercise was historic in scope, including posthumous pardons for nationalist Sir Herbert Macaulay (wrongly convicted by British colonial authorities in 1913), writer and activist Ken Saro-Wiwa and the Ogoni Nine (executed in 1995), and Major General Mamman Vatsa (executed in 1986). Among the living beneficiaries were former lawmaker Hon. Farouk M. Lawan (corruption conviction), approximately 40 illegal miners, drug offenders, white-collar criminals, and foreigners.

Under Section 175 of Nigeria’s 1999 Constitution, the President may grant pardons, respites, or commutations after consultation with the Council of State. The provision gives substantial discretion, allowing pardons “either free or subject to lawful conditions.” No specific conditions were mentioned for Maryam’s pardon, suggesting it was granted unconditionally. A full presidential pardon typically removes the conviction from a person’s record and restores all civil rights.

Public Reaction

The case ignited fierce debate about domestic violence, gender, and justice throughout its eight-year trajectory. When the death sentence was announced in January 2020, Nigerian social media exploded with divided reactions.

Supporters of the death penalty declared “Good! She deserves it! An eye for an eye!” representing what observers described as the “most widespread and commonplace reaction.” Many felt the sentence delivered appropriate justice: “She should reap what she has sown.”

But critics raised troubling questions about gender bias in the justice system. One viral social media post charged: “If Maryam Sanda was the one killed by her husband, there wouldnt be a death sentence. Of 121 recorded cases from 2014-18 where women were allegedly killed by their husbands, how many men sentenced to death? NONE! ZERO! Our legal system is very misogynistic & entrenched in patriarchy.”

Others drew uncomfortable comparisons to terrorism: “Maryam Sanda sentenced to death for killing her husband…but Boko Haram members will be caught after killing & destroying properties, Nigeria govt will rehabilitate them & send them back to the society, it makes no sense.”

Three major human rights organisations, the Human Rights Writers Association, Society for Civic Education and Gender Equity, and Make A Difference, condemned the conviction as a “miscarriage of justice.”

They argued the case was based entirely on circumstantial evidence without any witness seeing Maryam stab her husband, without a murder weapon, and without a confessional statement.

They also accused Justice Halilu of procedural violations, including failing to rule on jurisdictional challenges before delivering judgment.

The children’s welfare became a recurring theme. “Maryam Sanda’s anger did not only end her husband’s life & get her a death by hanging it also will make her innocent child grow up with no parents,” one commenter noted. Many pleaded for clemency to spare the children from losing both parents to violence and state execution.

Where is Maryam Sanda Now?

Following the October 11, 2025, pardon announcement, Maryam Sanda was released from Suleja Medium Security Custodial Centre, where she had spent six years and eight months awaiting execution. But her current whereabouts remain unknown.

No statements, interviews, or public appearances from the now-37-year-old have been reported. No information has emerged about whether she has reunited with her two children or what her plans are for rebuilding her life, given that the pardon was announced less than 48 hours ago (as of October 12, 2025). Given the explosive controversy surrounding her case, she is likely maintaining a low profile, protected by her family from media attention.

Public reaction to the pardon is still emerging. Multiple news sources describe it as stirring “mixed reactions among Nigerians” and reopening “national conversations about justice, forgiveness, and rehabilitation.”

President Tinubu characterised the broader clemency exercise as reflecting his administration’s “commitment to justice sector reform and restorative justice,” emphasising that clemency is “a tool for rehabilitation, not retribution.”

The victim’s family, including Haliru Bello, former PDP National Chairman and Bilyaminu’s father, has not issued public statements about the pardon. Whether they support or oppose the decision to free their son’s killer remains unknown.

The killing occurred in that most private and dangerous of spaces, the marital home, where jealousy over nude photographs escalated into fatal violence. Bilyaminu Bello’s murder joined a grim statistic: reports indicated that between November 2017 and January 2020, 53 spouses were killed in Nigeria, 36 wives killed by husbands and 17 husbands killed by wives. Yet as critics noted, death sentences for husbands who kill wives remain vanishingly rare.

Two children grow up knowing their father died violently at their mother’s hand, and their mother was nearly killed by the state’s judgment. Whether Maryam Sanda can rebuild a life after death row, whether her children can heal from unimaginable trauma, and whether Nigerian society can address the root causes of domestic violence remain open questions.